This is an AI translation from the original Chinese version. Editor’s Note:

Chen Teng from Sohu’s “Back Window Studio” has been closely observing the courtroom proceedings of the largest drug lord in history in New York.

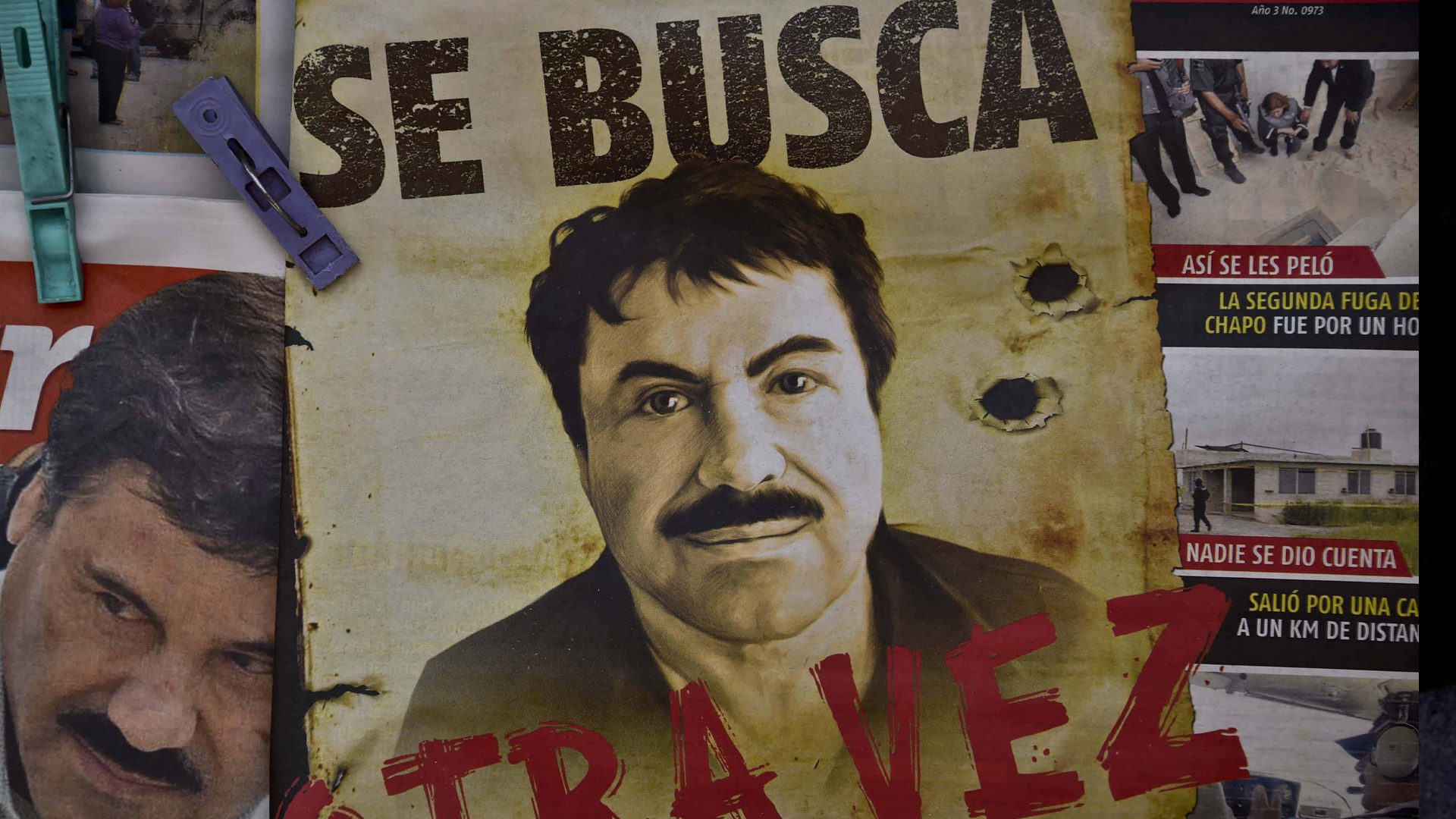

The defendant, known in the underworld as “El Chapo,” is a Mexican drug kingpin whose story is filled with legend. Recently, a film based on his experiences has been released. In fact, the courtroom itself has become another stage filled with noise and absurdity.

In a previous observation piece titled “The Trial of the Largest Drug Lord in History,” Chen Teng narrated the complex situation and interests surrounding the American judicial system, commercial media, and the Mexican drug trade through the courtroom proceedings and the past of “El Chapo.”

This time, the author continues to keenly capture the courtroom drama, depicting how the excessive exercise of power by the U.S. and the subtle manipulation of truth by the defense attorney clash in this “desperate struggle.”

After three months of trial and jury deliberation, “El Chapo” was convicted on ten charges, including operating a continuing criminal enterprise, international drug manufacturing and distribution, drug conspiracy, illegal use of firearms, and money laundering.

As the trial progressed, we couldn’t help but question: How has what is considered the most sophisticated judicial design in modern society reached the edge of embarrassing chaos? And who should deliver a fair judgment on the crimes?

By Chen Teng

Edited by Sun Junbin

Uncle Sam’s mighty fist ultimately defeated the largest drug lord in history, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán—this man, who has roamed the underworld for forty years, with business tentacles reaching as far as the United States and as distant as China and Africa, surrounded by various legends.

On February 12, 2019, after three months of dramatic courtroom proceedings and six days of jury deliberation, twelve jurors unanimously declared “El Chapo” guilty. Reports indicate that, for safety reasons, the twelve jurors, who remain anonymous, kept their heads down and did not dare to look at the man they had deemed guilty. “El Chapo,” who often appeared like an uncle selling watermelons under a sunshade, showed a look of surprise in court for perhaps the first time.

In his surprise, if part of it was an act, another part was likely disbelief that the luxurious defense team he hired for five million shiny dollars would face such a day of reckoning: all ten charges, including operating a continuing criminal enterprise, international drug manufacturing and distribution, drug conspiracy, illegal use of firearms, and money laundering, were upheld. This team of lawyers, known for successfully defending drug lords and mobsters, had always appeared confident and dedicated to manipulating the truth to counter the immense power of the U.S. government: the prosecution, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the subservience of small Latin American countries, and the early media verdicts labeling “El Chapo” as a “criminal” and “murderous maniac.”

This was not a battle of equals: the U.S. government spent fifty million dollars, while “El Chapo” only spent five million; the government called in fifty-six witnesses, while “El Chapo” brought in just one; the government took three months to present evidence, while the defense team only took thirty minutes. However, this does not diminish the fact that it was a difficult trial. The prosecution stated in their closing arguments, “We could find fourteen witnesses at random to prove ‘El Chapo’ guilty.” Yet, they ultimately brought in fifty-six.

In the final stages of the trial, the excessive exercise of power and cunning manipulation of truth became irreconcilable. If this desperate struggle was a hellish battle, the flames would reach the sky.

The courtroom was packed with “spectators,” including media reporters who seemed to have come with popcorn, and the actress who played “El Chapo” in the TV series “Narcos: Mexico.” The actress, Edda, said she came to see “El Chapo” in person and learn from him, as there was too little video material available online. In court, “El Chapo” nodded and smiled at her. Edda remarked, “I was a bit nervous, not sure what to do.” Indeed, the imitation was lacking.

Of course, Edda was not the only one trying to imitate. According to the Daily Beast, a wanted criminal defendant even sat in the family section reserved for “El Chapo’s” beautiful beauty queen wife. It wasn’t until the court noticed something was amiss and tried to remove him that this impostor insisted he was a relative of “El Chapo” and that the court had no right to do so. Ultimately, he was escorted out.

However, many people wanted to see “El Chapo” in person for various reasons. At the last moment, some, fearing they would go mad from missing the live event, took to a different path of madness—spending the night in sleeping bags outside the courthouse in sub-zero temperatures.

On January 17, when I arrived early in the morning, the courtroom was already full, and I was told I could only watch a video live stream from a room across the hall. The downside of this half-experience was that I couldn’t see the jury or the audience, especially the reactions of “El Chapo’s” wife. Frustrated, I approached a burly security guard standing at the courtroom entrance.

“If a seat opens up later…”

“No seats.”

“If there is one…”

“No seats.”

“I mean…”

“No seats.”

“Can you tell me?”

“No seats.”

“I…”

“No seats.”

As the trial neared its conclusion, the security guard became much more aggressive. It seemed that if I said one more word, I would be escorted away. Reluctantly, I returned to the video live stream room. This room usually had few people, but that day it was packed with thirty chattering reporters, a dozen spectators, and staff occasionally shouting “Sit down!” to keep everyone calm. I thought perhaps something unexpected would happen here.

At 9:25, “El Chapo” entered the courtroom. It was as if he was preparing for battle, embracing and shaking hands with his three main defense attorneys for encouragement. The lawyer known for his comedic talent, “Voldemort,” held onto “El Chapo’s” hand for an especially long time, then extended his other hand to pat “El Chapo’s” hand firmly, clearly conveying confidence—”Don’t worry, brother, we’ve got your back.”

What they were up against was the testimony of U.S. Drug Enforcement Agent Victor, who captured “El Chapo” in 2014. He forced “El Chapo” to kneel before him, confirming his identity by exclaiming, “Damn it! It’s you! It’s you!” This agent seemed particularly fond of American blockbuster narratives, leading the audience into a spy thriller reminiscent of “Capturing Bin Laden”—”Capturing the Drug Lord.”

Like all excellent spy agents, this American hero emphasized his ability to find breakthroughs in the smallest clues. He began with a person nicknamed “Nose,” who was “El Chapo’s” assistant and might know his whereabouts.

To this end, he traveled to the stronghold of the Sinaloa drug cartel, the city of Culiacán. The Spanish founders of this city share the same noble surname as “El Chapo,” Guzmán. Today, this city, which has been involved in drug trafficking since the 1960s, is filled with casinos, jewelry stores, and luxury car showrooms.

There are not many foreign tourists here, but there is a significant Sinaloa style, such as drug ballads that often foreshadow who the next target of the drug lord will be, the rampant traffic, or the rare sight of bulletproof graves.

The high-tech security bulletproof grave even has air conditioning (Image source: AFP/Getty Images).

When the American hero came to catch “Nose,” he stumbled upon a big party that blocked an entire street. He was completely confused about who “Nose” was: “Is it Big Nose? Little Nose? No Nose?” The audience and reporters burst into laughter.

What he knew as “Nose” was less of a person and more of a code extracted from a Blackberry phone by intelligence agencies. Within the drug trafficking organization, communication mainly relied on Blackberry phones. Each Blackberry had a unique code, which meant that if anyone’s phone had Nose’s code, they could confirm who Nose was without having to sift through a crowd to see the size or shape of anyone’s nose. Not to mention, Nose was called that because his nose was crooked.

The American hero ordered the partygoers to lie down and checked their phones one by one. However, none of the codes were correct.

“Suddenly, a woman shouted that she needed to check on her baby. I felt something was off, so I followed her to a nearby house. She was tightly holding the baby. We rushed in and snatched the baby from her hands. Just then, a Blackberry phone fell to the ground!” The audience in the courtroom gasped as the Blackberry hit the floor.

The code on that phone belonged to Nose. Shortly after, the American hero discovered Nose in the bedroom.

This crooked-nosed individual turned out to be a Mexican agent who later defected to join the drug trafficking organization, becoming the assistant to the Short One. After being captured, Nose easily flipped the situation and led the American hero to the Short One’s hideout in Culiacán. After breaking through a reinforced metal door in ten minutes, the American hero continuously instructed his colleagues, “Don’t wander around, go straight to the master bedroom.”

Suddenly, there was a series of loud noises. He heard his colleagues on the intercom saying, “Tunnel, tunnel, tunnel.” With Nose’s help, they connected two wires to unlock the entrance to a tunnel hidden beneath the bathtub in the bedroom.

For the short-statured Short One, the tunnel was like his Harry Potter invisibility cloak. After inventing the first cross-border drug trafficking tunnel in 1989, tons of drugs flowed into the United States like cheerful little trains.

Over the next 30 years, the Short One, who invented the invisibility cloak, figured out that tunnels could be built not only under warehouses or in deserts but anywhere there was ground—such as the graveyards of those who thought they would never be disturbed again. According to The New Yorker, digging tunnels faced various challenges like collapses, water seepage, and oxygen deprivation. The Short One hired architects for design and published fake ads to recruit diggers. When the diggers arrived on-site, his men would tell them to either dig or their families would die. In a newly discovered high-end tunnel over 800 meters long in 2016, there were already cement floors, lights, tracks for vehicles, ventilation systems, and even an elevator. Drug traffickers had even begun exploring the use of drainage systems, diving equipment, drones, and slingshots to shoot drugs over the border wall.

Once, an American agent tried to drill three feet into the ground to see if anything was amiss. Accidentally, he hit a faucet, and suddenly, like magic, a pool table rose, revealing a larger basement with an entrance to a tunnel.

The Short One seemed to enjoy shocking the world in various ways, leaving a mark in history. Besides negotiating with actor Sean Penn to make a movie about himself, in 2015, he escaped from Mexico’s highest-security prison through a tunnel. On the night of this world-famous escape, after changing his shoes, he walked to the shower area, squatted under a cement partition, and disappeared. He slid back to his drug empire on a small tunnel train, traveling 1,600 meters.

He was famously known for having multiple escape routes. Once, during a court hearing in New York, the lights suddenly went out, plunging the courtroom into darkness. When the lights came back on, someone suddenly shouted, “He ran away,” causing everyone to look at the Short One’s spot.

Fortunately, he was still there.

In comparison to the astonishing imagination of Mexican drug lords, American President Trump, who loved McDonald’s burgers and Coke, seemed foolish. His most vigorous strategy for dealing with border issues was probably to build a wall along the 3,000-kilometer U.S.-Mexico border. Regarding the question of “how deep the wall needs to go to stop the Short One’s tunnels,” if Trump had any knowledge of tunnels, he should have felt uneasy. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security stated that the wall could only be 9 meters high above ground and 2 meters deep, although they did not explain why. However, drug trafficking tunnels have been found to go as deep as 10 meters. By 2016, at least 224 tunnels had already been discovered.

At the capture site, the Short One once again slipped into his invisibility cloak. The awkward part was that the American hero was too tall at 1.88 meters to fit into the tunnel specifically dug for the 1.68-meter Short One.

“I asked our brave colleagues, ‘Who is willing to take off all their gear and weapons to go down the tunnel?'” Every one of my colleagues volunteered. Past experiences taught the American hero that in such special operations, he could no longer cooperate with Mexican federal or local police, as those corrupt individuals had already been bought off by the Short One. He could only turn to the Mexican Navy to find an elite unit.

“I also had them bring GoPro cameras to record the video,” the American hero continued.

Just then, the sound in the live broadcast room suddenly cut out. Everyone was momentarily confused, and then a male reporter dashed out of the studio to get the staff to fix the broken system quickly. The entire press area erupted in excitement, shouting at him, “Run! Run!”

A few minutes later, when the sound returned, the American hero said, “The tunnel is extremely, extremely hot.”

They searched from one house to another, from one tunnel to another, finding rocket-propelled grenades and extremely deadly evidence—a diamond-encrusted handgun with the initials of the Short One, JGL, 2,800 packages of stimulants, and some plastic bananas filled with cocaine powder.

However, the only thing they never saw was the Short One himself. Sometimes Nose would say, “The Short One is just ahead.” Yet in the end, they lost track of him. Perhaps the only purpose of this raid was to drive the Short One out of his lair in Culiacán.

Subsequently, the American hero received intelligence that the Short One had moved to Mazatlán, a city 200 kilometers away with a completely different atmosphere. This was a leisurely tourist city, the birthplace of Sinaloa Banda music, known for its beaches and diverse cultural activities. The American hero rushed over. To make himself look like a tourist, he took over twenty members of the Mexican Navy participating in the operation to a local Walmart to buy beach shorts and shirts, strolling along the beach.

(Image from Culiacán, the Short One’s lair, to Mazatlán. Image source: Google Maps)

They then locked onto the vacation-style Miramar Hotel.

“There were over twenty people searching the hotel, which is a very small team considering we were looking for a ten-story hotel with various different passages and entrances,” the American hero repeatedly emphasized this point, as it demonstrated his strength and bravery—using so few people to capture what they deemed “the biggest drug dealer in history.”

“I ordered my team to keep an eye on the side of the hotel to prevent anyone from jumping out of the window to escape.” Suddenly, the American hero, filled with a sense of helplessness regarding the tunnels, said, “All I hope is that there are no more tunnels in this hotel.”

“Suddenly, I heard ‘777, 777.'” This code meant, “We have caught someone; come confirm quickly.”

“I arrived in the basement, stunned, looking at the dwarf, saying, ‘Oh my God, Eres tu! Eres tu!'” (In Spanish, it means, “It’s you! It’s you!”)

Thus, the American hero captured the dwarf. At that time, there were also two little infants and his wife, Emma, along with a nanny; no one had weapons, and no one had drugs.

The “American hero” was undermined in court.

After the American hero finished his testimony, the judge announced a 15-minute recess. Reporters and audience members left to use the restroom or grab coffee, except for three main defense attorneys. They gathered at the questioning stand to discuss, as it was now their turn to present. Clearly, they needed to dismantle the American hero’s testimony, and they showed no signs of panic.

Suddenly, a short woman in her fifties sat down beside me. She wore an old coat and carried a cheap, faded red bag. Out of curiosity, I started a conversation with her, as it seemed unlikely that someone with financial difficulties would have the time to attend a court session on a weekday. She told me she was a lawyer and that a client would be testifying shortly. The business card she handed me simply read, “Heather Shana, Lawyer, Phone, Email,” with no design, just plain black text on white paper, and the card was a bit dirty. I thought, what kind of witness is so unfortunate that even their lawyer ends up in this insignificant courtroom?

When the recess ended, defense attorney Balarezo took the stand. His head was shiny and round, his belly protruding, and he had a “don’t mess with me” demeanor. He was the lawyer mentioned in the previous article, who had been accused of posting “death music” threats to witnesses on Twitter; let’s call him the “Menacing Gourd.”

“Good morning, sir. How are you today?” the Menacing Gourd began politely. He held materials and walked down from the questioning stand. Unlike the prosecution attorney, who remained fixed at the podium, he walked back and forth in the courtroom while asking questions.

“Did you see that? By walking around like that, he can attract the attention of the entire court, and the jury will focus on him,” the female lawyer Shana leaned over to tell me.

“What was your role in the raid team?”

“I only provided information and advice inside.”

“Did you carry a gun?”

“Objection,” the defense attorney interjected.

“Objection sustained,” the judge replied.

Due to sovereignty issues, in gun-controlled Mexico, U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agents are not allowed to carry firearms. This question was as sensitive as asking whether U.S. agents could carry guns in China. But for agents coming from a country where there is one gun per person, executing a mission without a gun feels akin to going out without clothes.

The American hero no longer exhibited the 007 bravado and confidence he had at the beginning of the trial. He resembled a deflated balloon, losing air rapidly. His responses became less fluent, his voice less resonant, and he had to clear his throat every few questions; the sound of him drinking water could be heard in the courtroom.

“The one nicknamed ‘May’ is the leader of the Sinaloa drug cartel,” the Menacing Gourd stated, adhering to his defense theory that “the dwarf is not the leader, just a scapegoat.”

“One of the leaders,” the American hero quickly interjected.

“May is very dangerous.” The Menacing Gourd paused, took a couple of steps to let the audience and jury digest this statement before continuing, “So you spent several days looking for May and his subordinates, but you didn’t find May, so you started looking for the dwarf?”

“We went there because the intelligence department told me the dwarf was there.”

“Please answer the question directly.”

“Objection.”

“Objection sustained,” the judge said.

“Did you hear someone say the dwarf was right in front?”

“Yes.”

“Does hearing the Navy say someone is in front prove that someone is indeed there?” “Did you see the dwarf?” “Did you hear the dwarf’s voice?” “Is there any evidence that this is the dwarf’s house?” “Does the house have any identification related to the dwarf? Any official documents?”

The prosecution began to continuously object to the questions. The judge repeatedly stated objections were sustained, overruled, or sustained again. The pace was so fast that it felt like the entire courtroom was simultaneously setting off several strings of firecrackers. After several rounds of exchanges, a female prosecutor began to cough violently, momentarily interrupting the court. It seemed unintentional, but who knows? The Menacing Gourd paused and kindly asked the prosecutor if she needed a break. He tried to appear like a kind and considerate gentleman. The prosecution declined, and the Menacing Gourd continued his bombardment, while the prosecution maintained a high frequency of objections. At one point, after the prosecution finished an objection, the judge remarked, “The defense hasn’t even posed a question yet.” The entire courtroom erupted in laughter.

Shana leaned over, excitedly waving her hand, saying, “If it were me, I would ask one question in fifteen different ways, constantly forcing the prosecution to object.”

I asked why.

She replied, “This would make the prosecution look foolish because it would lead the jury to believe they are trying to hide information.”

“When you captured the dwarf in the hotel, besides his wife Emma and the two infants, were there any other people?”

“No.”

“Did they have weapons?”

“Objection.”

“Objection overruled.”

“No.”

“Did you hear any gunshots?”

“No.”

“The dwarf never resisted, right?”

“Objection.”

“Objection overruled.”

“They did not resist at all.”

This scene sounded as if the dwarf and his wife and daughter were on vacation when they were inexplicably captured.

The Menacing Gourd continued, “These Mexican Navy personnel are all very well trained, right?”

“Yes.”

“This wasn’t their first capture operation, was it?”

“It was.”

“They needed you, an American, to tell them that this person in front of them is the dwarf?”

“Yes.”

The Menacing Gourd let the air freeze for a few seconds, mixed with disdain and mockery, and asked, “This notorious drug lord in Mexico?”

Thus, after half an hour of tightly structured questioning, a brisk pace, terrifying implications, and the precise art of leaving things unsaid, I, as an audience member, felt the story had transformed: the agents went to capture May but couldn’t find him, so they turned to capture the weaker dwarf instead. However, in the super tunnel, they didn’t even see the dwarf’s shadow and assumed they had caught him. Later, the agents went to a tourist city, wearing Walmart beach shorts, and inexplicably captured the dwarf, who was on vacation with his wife and daughter, and whom even the Mexican Navy barely recognized, and who was unarmed.

Regarding the defense attorney’s relentless guidance that “May is the real leader,” the judge had to prohibit the defense attorney’s deliberate leading questions, stating that such assertions were highly misleading, as there can be more than one leader.

Regardless, after the cross-examination, the dwarf’s lawyers gained some advantage.

It is too early to draw conclusions.

Betrayed Lover

During lunch, I saw the dwarf’s 29-year-old wife, Emma, in the restaurant.

According to reports, during the more than three months of the trial, she almost attended every day, facing the ups and downs of the courtroom alongside her husband. However, this afternoon, the couple had to face a witness, a 28-year-old woman with a beautiful name, Lope, which signifies a beautiful soul and mind.

I wonder if Emma will feel restless upon seeing this witness. In any case, when Lope’s name was called in the courtroom after the lunch break, the press section became agitated. A young female reporter, dressed in leopard print and sporting bright red lips, resembling Marilyn Monroe, had been distractedly fidgeting or adjusting her dyed silver-gray hair, or laughing with a handsome male reporter next to her. But at that moment, she sat up straight with excitement. Meanwhile, the female lawyer beside me was extremely tense. She clasped her hands tightly, half-kneeling and half-standing against the front row of chairs, telling me she was praying to the judge as if he were God.

“What is your relationship with the Dwarf?” the prosecution asked Lope.

“To be honest, I am still very confused. I thought we were two people together because we loved each other.”

The courtroom erupted in astonishment, with everyone wearing expressions of surprise. This reaction was quite different from the drowsy atmosphere I had observed earlier in the trial—the frustrated prosecution seemed to have learned from their mistakes. Faced with the dramatic defense lawyers, the prosecution decided to let the jury enjoy a soap opera after their espionage thriller.

Regarding love and indifference, Lope repeatedly mentioned in court, “Sometimes I love him, sometimes I don’t, because his attitude towards me is good sometimes and bad at other times,” and “I am really confused.” She added, “Sometimes I deliberately mess up business to make him unhappy, forcing him to come find me.” In this theater where truth and falsehood were indistinguishable, her repeated discussions of love elicited laughter from the audience.

The prosecution had Lope recount the details of her life with the Dwarf: their relationship began in 2011 and ended in 2014. She described how she communicated with the Dwarf through encrypted BlackBerry phones, climbed towers daily to get a signal, and how every two weeks, the Dwarf’s subordinates would come to change her phone, as well as how she took care of his daily needs.

“There was a time when we lived together, and I would help him buy everything he needed, from underwear to shampoo. His pants size was 32, but I would always go to the tailor to have them altered to a 28.” While saying this, Lope referred to the Dwarf as her husband.

Lope’s description carried a natural tragic quality that evoked strong sympathy. Like the Dwarf, Lope grew up in poverty in the mountainous region of Sinaloa, Mexico. At the age of eight, she began selling Mexican fried pies on the roadside, and by ten, she was helping to pick tomatoes and cucumbers. However, like many girls from poor families, she easily slipped into a downward spiral. The drug-laden hills of Sinaloa paved the way for her life’s decline. By the age of sixteen, Lope began living with someone from a marijuana-growing area but soon suffered abuse from her husband and his family.

This misfortune did not prevent another calamity from arriving—poor girls’ beauty often carries ominous signs. Lope grew up to be a local beauty queen, just like the Dwarf’s wife, Emma. At twenty-one, she met the Dwarf, though the details of their meeting were not extensively reported. The Dwarf told her he wanted a more stable relationship and asked for her help in acquiring marijuana, as Lope had lived in the marijuana region for a long time and knew people there.

“My love, how’s business today?” the prosecution projected a BlackBerry message in which the Dwarf asked Lope.

“Non-stop, baby.”

They were discussing how Lope was busy acquiring marijuana for the Dwarf: 400 kilograms of marijuana wouldn’t fit on the plane, so they could only load over 300 kilograms this time, and the next batch would be larger, etc. Each message presented in court ended with terms of endearment like “my love,” “I love you,” “baby,” or emoji hearts. This level of detail and intimacy made it nearly impossible for the defense to undermine their relationship, thus enhancing the credibility of Lope’s testimony.

Additionally, the messages revealed that the Dwarf seemed quite adept with women. He had three wives and an unknown number of lovers, with over a dozen children. Court testimony mentioned that his wife, Emma, had once helped him escape from prison. Meanwhile, Lope, during the Dwarf’s incarceration in Mexico, visited him under a false identity while pregnant.

At that time, Lope’s identity was highly sensitive, as she was a local councilwoman. In court, when discussing her election, she spoke with pride, saying, “I won a lot of votes to become a councilwoman.” Yet, this legislator willingly took such a significant risk to visit the Dwarf. Photos from her prison visits were later leaked, exposing her relationship with the Dwarf and becoming a major scandal. She claimed her visits were to discuss personal matters because the child she was carrying was the Dwarf’s. However, she was still expelled from her position. Nevertheless, it seemed Lope was quite popular locally, with even a lawyer stepping forward to say she was just “too emotional about the wrong person.”

In court, she portrayed herself as a person full of emotion and compassion: “Sometimes the quality of the marijuana is poor, and I would still take it because I know how poor the people growing it are. They put in so much labor but receive so little in return.”

In 2017, Lope was arrested at the border for conspiracy involving five kilograms of cocaine. Initially, she did not plead guilty, but in October 2018, just a month before the Dwarf’s trial began, she finally confessed and is now awaiting sentencing in prison. The prosecution is seeking a minimum of 20 years or life imprisonment for her—this is the maximum penalty for conspiracy involving cocaine, typically reserved for drug lords like the Dwarf. However, the prosecution informed Lope that if she cooperated and testified against the Dwarf, she could receive a reduced sentence. To ensure the effectiveness of her testimony, the prosecution met with her twenty to thirty times.

Convincing suspects to provide testimony in exchange for reduced sentences is a common practice for U.S. prosecutors and the government. Lope had no power or influence and could not afford a private lawyer, so she, like every poor person, had to rely on a public defender assigned to her by the government. However, with so many poor people, public defenders often have overwhelming workloads and are not well-off, much like the lawyer I saw, Heather. Therefore, since they cannot spend more time defending the poor, they often have to persuade them to plead guilty (even if innocent) in exchange for lighter sentences.

In Lope’s testimony, I did not see any evidence of her conspiring with the Dwarf regarding cocaine; it was all about marijuana.

So during the break, I asked Lope’s lawyer, Heather, “Why are they prosecuting her with such a heavy sentence?”

“Because the government people are bastards,” she said through gritted teeth.

“How did you end up in this courtroom?”

She replied, “I’ve been defending for over 40 years, and this is the first time I’ve encountered such a situation: the prosecution people won’t let me into the courtroom. They think my presence will influence the witness.”

In our casual conversation, Heather told me that when she was younger, she initially went to teach seven or eight-year-old children. The parents of those children were all serving time in prison, and they came from poor backgrounds. One day, she went home and called her mother, crying, “These poor kids are so pitiful. Thinking about the privileges of rich kids, I feel this world is so unfair.” Her mother told her, “If during my upbringing of you, you felt that this world was fair, then I would have failed as a parent.”

Later, she went to law school and began a life defending powerless criminal suspects.

At that moment, a tragic cry suddenly erupted in the live broadcast room, which was soon silenced. The previously noisy studio fell silent: it was Lopez who was crying. Heather wore a complex expression.

This is the fate of true underdogs. On one side is a powerful government threatening lifelong imprisonment; on the other is the leader of the Sinaloa drug cartel, who despises betrayal. The word “murder” is not unfamiliar to her, having experienced the murder of a loved one.

“You see, the mafia kills those who don’t pay or betray them. But if you are serious, nothing will happen. I love you,” the Underdog once texted Lopez.

Lopez replied, “I’m not afraid, my dear. I’ve thought about some things before, and I know I won’t do anything bad. On the contrary, I think this is a good thing, especially being with you, because you have helped the ranch a lot. I am proud of you; I hold my head high, guided by you, my dear. If you like what I do and want me to continue, I will help you until you want me to stop. I enjoy this; at least I feel useful.”

Once again, she heard the Underdog order the murder of his betraying cousin. She saw him angrily declare, “All who betray me must die, whether they are family or women.”

The Underdog escaped from the tunnel completely naked.

After the recess, Lopez regained her composure, and the prosecution began to have her recount the most deadly story: why American heroes failed to capture the Underdog in Culiacán. That night, Lopez was with the Underdog.

That night, while Lopez and the Underdog were asleep, she suddenly heard a loud noise at the door. The Underdog took Lopez to the bathroom. He lifted the bathtub and had her jump into a dark tunnel with him.

“I was terrified and didn’t dare to jump.”

But in the end, she did go down, and a valve separated the tunnel from the outside world. The tunnel was low and dark.

“How long is the tunnel?”

“Long enough to give me psychological trauma.”

“What was the Underdog wearing when he escaped?”

“He was completely naked.”

“Hahahahaha,” the entire courtroom erupted in laughter.

The headlines about the trial that day were all similar to “The Underdog Escapes Naked with His Lover through a Tunnel.”

Thus, through Lopez’s testimony, the prosecution dismantled the carefully orchestrated cross-examination by the defense.

“So does she love the Underdog or not?” I asked Lopez’s lawyer.

She paused and said, “I can only tell you that she is not a willing lover.”

“But she seems to be volunteering when she helps him with business, and she appears very cheerful.”

“The Underdog is a powerful man. If she doesn’t help him, he will always find her.”

The day after Lopez finished her testimony, the Underdog and his wife Emma appeared in court wearing velvet red outfits, interpreted as a declaration of their united front.

Later, according to Vice News, during the cross-examination of Lopez, the narrative shifted to the Underdog never giving Lopez money for marijuana, and if he were truly such a drug lord, why would Lopez need permission from a local small-time grower when helping him buy marijuana?

“This is a big show.”

Thus, in this so-called trial of the century, the U.S. government spared no effort to convict the Underdog, while the defense lawyers wielded the law as a weapon to ensure he received a fair trial.

The truth, like love, is one of the hardest things to obtain in this world.

Even reporters who sat in the courtroom almost every day found it difficult to fully digest the power struggles at play. During each break, everyone chattered about their notes. In the end, more balanced media outlets would strive to write about the challenging cross-examination processes, while more reckless ones would simply abandon nuance, reporting any dramatic detail from witnesses as fact. This is what is known as a media trial. Therefore, the judge repeatedly emphasized that jurors were not allowed to look up any information related to the case online.

However, considering that the jurors, who were legally illiterate, had to sit in court for over three months, making a judgment based on complex, sometimes boring, and often convoluted information filled with sophistry and conspiracy theories, it seemed incredibly difficult for them. Under immense pressure, it is easy for people to give up or take shortcuts.

After both the prosecution and defense had completely presented their evidence, before closing arguments, a female juror even asked the judge’s clerk if she needed to know whether the defendant had paid his lawyer, as it was important to her.

As the deliberation phase approached, the media had already set up long tents outside the courthouse, ready with cameras.

“This is a big show, a scam; you all know what’s going on,” said the Underdog’s defense attorney, Richman, in his closing argument. He accused the entire process of being scripted, stating, “But a house built on a rotten foundation cannot stand for long.”

Richman continued, “These prosecution witnesses have committed lies, theft, fraud, drug trafficking, and murder. If the Underdog is convicted, those cooperating with the prosecution will receive much lighter sentences.” He added, “The government, in its pursuit of the Underdog, has sacrificed fairness, justice, law, and morality.”

The prosecution countered, “The defense attorney is pointing fingers everywhere, except at the solid evidence. This is a deliberate attempt to mislead you. Look at who is on trial here. Who has a diamond-encrusted gun? Who can have an entire network of escape tunnels? Who has over a thousand meters of escape tunnels? Common sense tells you it is the leader of the Sinaloa drug cartel.”

Richman was undeterred, “This brother has no money! If, as the witness said, he had a hundred million dollars to bribe the Mexican president, why would he keep getting caught like a rabbit?”

Richman then began to sing along with the prevailing narrative in American society that “America is the greatest country in the world”: “You know what? Before you came here, the government made deals with these bad guys (the witnesses). Do you think this is the country you live in?” He then invoked the American ideal of individual heroism, saying, “These witnesses lie repeatedly, but the government does not stop them. You can stop them.”

“I am here fighting for a person’s life. I am trying to fill the walls of the courtroom with reasonable doubt,” Richman said, according to NPR. The New York Post, known for its flamboyant style, wrote, “By the end, Richman was almost in tears.”

Richman concluded, “I urge you to look into your hearts. If you have any doubts, do not let them slip away easily. You do not have to believe the legends about the Underdog. No, no, no, he is innocent.”

The prosecution responded, “You must first believe that the Underdog is the most unfortunate person in the world to believe the defense attorney’s words.”

The story returns to its distant origins.

In fact, the drug war between the United States and Mexico is inextricably linked to distant China.

Two centuries ago, in the pursuit of capital, the British Empire left behind a demon in China—opium. The Chinese, possessed by this demon, were later attracted by the gold rush promoted by America, traveling far to build railroads.

They repaired the railway known as a miracle, which also brought about the decline of the opium-smoking culture.

After the railway was completed, American society accused Chinese workers of taking jobs that white people were unwilling to do. They expelled the Chinese with the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act, leading some workers to migrate south to the welcoming Mexico, arriving in Sinaloa, a place with mountain breezes and ocean air. They learned the local language and adopted local names, such as the famous Patricio Hong or Felipe Wong. Then, they allowed poppies to bloom all over Sinaloa. The opium was subsequently smuggled into the United States.

A century later, Sinaloa gave rise to the largest drug lord in history, known in the underworld as “El Chapo,” Joaquín Guzmán.

After El Chapo was convicted, American politicians reacted strongly. The Republicans said they wanted El Chapo to pay for the wall. A notorious figure tweeted that the person making that statement was a fool. The Democrats argued that this case showed that building the wall was useless. The prosecution waved the flag of victory, claiming it was a triumph in the war on drugs—this mainstream narrative, indeed, was grand and hollow, stirring the hearts of many.

In this so-called U.S.-Mexico drug war, America has always emphasized how much drugs Mexico sends to the U.S. each year, harming countless Americans and costing billions. However, for Mexico, it is about how many firearms the U.S. sells to Mexico each year, fueling drug trafficking and gang violence. According to a report by the Brookings Institution, between 2009 and 2014, 70% of the firearms seized in Mexico came from the United States, totaling over 70,000. Not to mention, these firearms are just a fraction of all the crime-related weapons.

Drug users in the U.S. are victims, and those shot in Mexico are also victims. The reason Mexico can continuously transport drugs to the U.S. is that America is the largest drug market in the world. Many Americans start using drugs from prescription painkillers approved by the FDA, which contain excessive amounts of opiates and fentanyl. After I once took a prescription painkiller in the U.S. that cost about 35 RMB, feeling invigorated and unusually excited, I have never dared to take another painkiller since.

As this grand trial, showcasing American wealth and power, came to a close, the sea breeze and mountain winds continued to blow over the poppies and marijuana in Sinaloa. As long as there is demand in the vast market, when one dwarf falls, another will rise. And this legendary dwarf, perhaps, has not yet reached the end of his life—he plans to appeal.

Perhaps one day, when the young men emerging from the impoverished ridges of Sinaloa no longer have to rely on earning $100 for their older brother’s lookout to support themselves and their families, the poppies and marijuana will finally have a chance to leave this charming yet sinful land.

Ultimately, as the saying goes, Mexico is too far from God and too close to the United States.