(This is an AI translation from the original Chinese version.) Written by Chen Teng / Edited by Sun Junbin

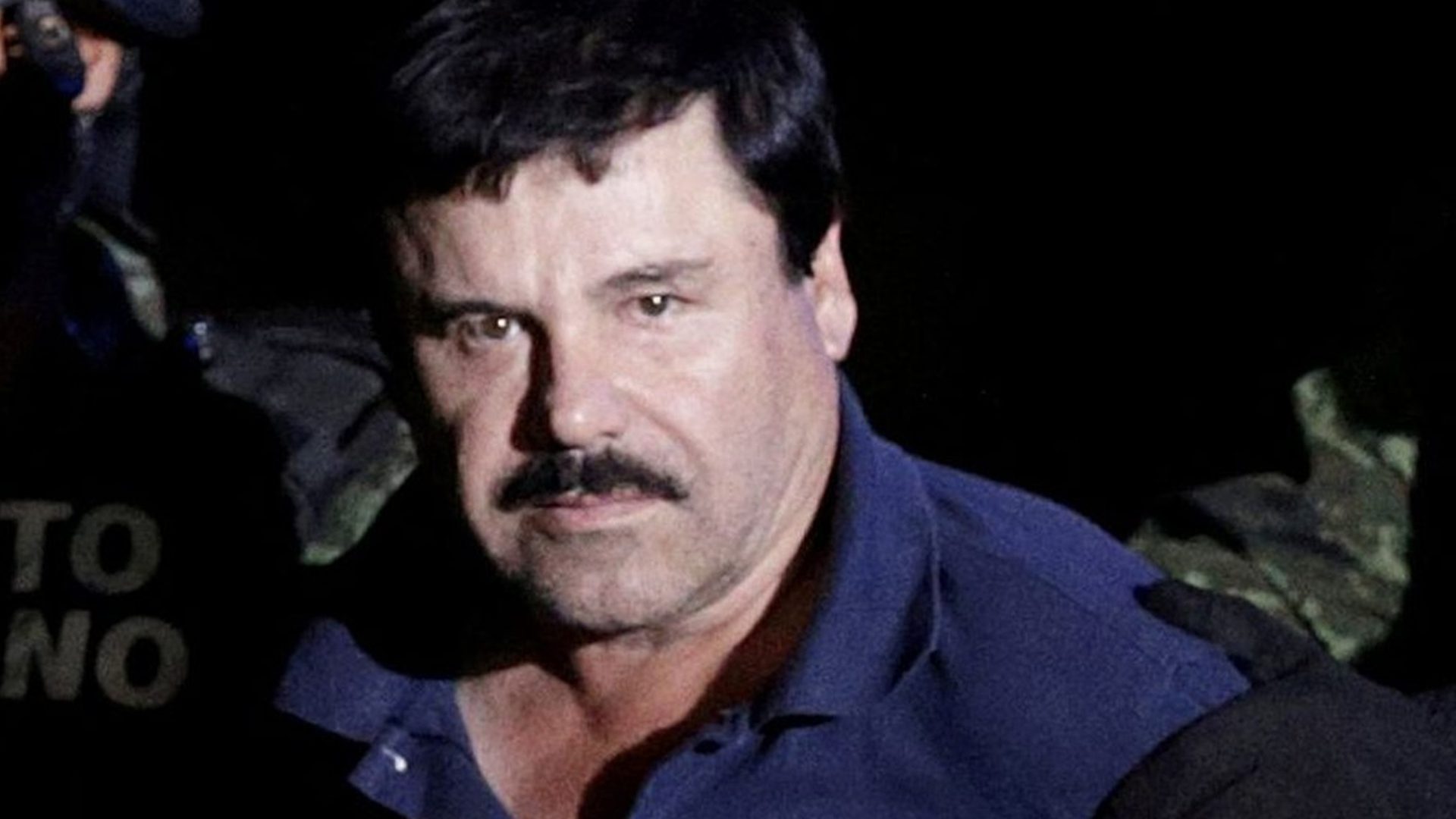

The man widely known as “Shorty” (Spanish “El Chapo”), was born in a poor village in Mexico. The exact year is unconfirmed, but he is believed to be around 60 years old. He has a gentle demeanor, and if you saw him walking down the street, you might mistake him for a friendly uncle selling watermelons. However, on the morning of November 5th, 2018, the transportation of this man led to the complete shutdown of the Brooklyn Bridge in New York. Standing at only 168cm tall, he is labeled by the U.S. government as the “drug lord,” deemed “the most ruthless, dangerous, and feared man on Earth.”

On this day, Joaquín Guzmán, known as El Chapo, was brought to the Eastern District Federal Court in New York, where he would face a trial that could last up to four months.

The jury members were terrified.

The U.S. prosecution has spent $50 million on this case, preparing 300,000 pages of materials, 110,000 recordings, and hundreds of witnesses. The charges include leading a drug trafficking organization, participating in murders, money laundering, and 17 other federal felonies.

El Chapo denies all these charges. He has spent $5 million hiring a luxury legal team with an average age of about 55, hoping to walk out of the courtroom as an innocent free man.

In what may be the most expensive trial in U.S. history, the decision of El Chapo’s guilt or innocence rests with a jury of 12 laypersons. These 12 individuals were randomly selected by a computer from the voter rolls of the Eastern District of New York. This is the American version of “the eyes of the public are sharp”—the jury system.

For a long time, the jury system has been likened to “a ship sailing into a storm,” as it is often more unpredictable than a judge’s ruling. For example, in the famous O.J. Simpson murder case years ago, the defense ultimately won the jury’s unanimous opinion, and Simpson was acquitted, shocking the nation. As a star of the National Football League, Simpson spent about $3-6 million hiring a “dream team” of celebrity lawyers, including Harvard Law professors, to fight against a prosecution that cost taxpayers $9 million.

On December 20, at 9:30 AM Eastern Time, Judge Brian Cogan led everyone to stand as the 12 jurors entered. Among them were five men and seven women, dressed in ordinary clothes, resembling the typical uncles and aunts you might see at a market or colleagues in an office. The audience was filled with media and spectators, who, like me, woke up early on a cold winter morning just to secure a seat. After all, the line of people had started forming before dawn at the courthouse.

In the courtroom, it took me several minutes to identify El Chapo. This was different from my previous expectations; typically, defendants in domestic courts wear orange jumpsuits, flanked by two stern-looking bailiffs. But El Chapo was dressed in a suit, sitting neatly, though he appeared somewhat fatigued. He was not handcuffed and did not have to stand. Surrounding him was his dream defense team, seated at a 10-meter-long table covered with materials, facing the 12 lay jurors.

There was a debate in court about whether the identities of these 12 civilians should be kept confidential. El Chapo’s defense attorney argued, “This would leave the impression that El Chapo is a dangerous and frightening person.” This aligned with their defense strategy, which aimed to portray El Chapo not as the head of the Sinaloa drug cartel but as a low-ranking operative.

However, the Mexican judge who extradited El Chapo to the U.S. was shot dead while jogging one morning last October. Despite the various measures taken by the judge to protect the jury’s privacy, some candidates were so frightened upon learning they had been selected that they cried. The defense attorney opposed removing them from the jury, arguing, “If shedding a couple of tears allows someone to avoid serving, it would set a precedent for future cases.”

In this way, both the defense and prosecution can influence which candidates make it to the final 12-person jury. Supporting or opposing a candidate is not just a technical matter; it often feels like a gamble. In the Simpson case, the defense found that women were generally more inclined to vote for acquittal, while the prosecution believed women were more likely to sympathize with the murdered wife and vote guilty. Ultimately, the jury consisted of 10 women and 2 men, and the prosecution lost decisively.

While gender is not the only factor, perhaps El Chapo’s defense team believed that women who feared being killed after the trial would be more likely to vote not guilty. Regardless, the woman who cried in fear is still on the jury, facing the man who once made her weep.

As the trial began, the prosecution displayed photos on a projector, introducing seized evidence, including images of three rocket-propelled grenades, 40 hand grenades, and 17 bags containing a total of 403 kilograms of heroin. At first glance, this was indeed frightening. However, as the process continued, it felt more like a lengthy lecture on weapons and drug technology. By the first week, some jurors had already fallen asleep. Many of the audience members, including an elderly woman sitting behind me, spent most of their time dozing off in the corner.

Judge Brian, 64, with silver hair, had been spinning in his chair for over half an hour. Finally, after not hearing any evidence linking these weapons directly to El Chapo, he couldn’t help but interject, “Why are we looking at so many photos of rocket-propelled grenades?” He said, “This is truly a long journey.”

The prosecution’s attorney began to feel nervous, but it was like spending a fortune to take a big exam; they had to write something, even if it was a struggle for the audience.

About an hour later, the prosecution finally concluded their first round of evidence presentation, and I breathed a sigh of relief. At that moment, one of the defense attorneys, a shiny bald man, suddenly raised his arms to the sky, signaling “end,” and exclaimed with a mix of disdain and excitement, “Welcome! We have no issues to raise.”

This attorney, named William Purpura, has been described by the media as a lawyer with comedic talent. He indeed possesses excellent and well-timed acting skills—over-the-top but not enough to be thrown out of court. Each time the prosecution’s evidence was weak, he would spring into action to help the jury reinforce the impression that “the prosecution is weak.” At 63, William, wearing thin glasses, resembles “Voldemort” from the Harry Potter series.

According to the Baltimore Sun, in his youth, he was at the bottom of his class at Seton Hall University. He enjoyed hitchhiking to horse races, listening to jazz, and experiencing all the splendor of New York City in the 1970s. After graduating, he veered off to Indiana Dunes to race off-road vehicles, eventually landing a job at a law firm that laundered money for loan sharks.

He once saw Humphrey Bogart, the star of “Casablanca,” on a black-and-white screen say, “Tell the jurors not to blame the murderer; what causes these things is poverty, abuse, and neglect.” There is no evidence to suggest how much this statement influenced him, but “Voldemort” began his career as a defense attorney for “the worst of the worst.” He always worked alone, a lone wolf, but often managed to secure life sentences or reduced sentences of ten years for his clients, starting in 2006 when he began defending Latin American drug lords.

“Voldemort’s” comedic performances could indeed lighten the mood in the dreary courtroom, with a blend of black humor infused with Mexican rural characteristics, providing jurors with the thrill of watching a drug lord’s legendary film.

Witnesses reported that the Dwarf not only enjoyed taking small trains around his private zoo but also liked using trains to smuggle drugs into the United States. However, the ships carrying drugs always needed something to disguise their cargo; sometimes it was a pile of vegetables, sometimes it was a tank of cooking oil, and sometimes it was 150 sheep. Vegetables were easy to handle, often sold at rock-bottom prices, although this nearly caused a collapse of the local vegetable market. But bringing 150 stinky sheep into downtown Chicago was a different story. In desperation, the Dwarf’s men called a friend and gave him $10,000 to help with the situation.

Prosecution: Did he take all the sheep?

Underling: No.

Prosecution: Then where did the remaining sheep go?

Defense: Objection!

Judge: Objection sustained.

The fate of the remaining sheep became a mystery. The defense attorney might have been concerned that there were animal rights activists among the jurors, as the possibility of the remaining sheep being executed was not out of the question.

The Dwarf’s world consisted of vegetables, sheep, ranches, and mountains—this was the world he grew up in and continued to inhabit as an adult.

In 2015, after his second escape from prison, the Dwarf hid in the mountains, wearing a blue floral shirt, surrounded by clucking roosters. This was his first appearance in a non-custodial state during a media interview. In a video sent to Rolling Stone, the Dwarf said, “Life after escaping prison is very happy because there is so much freedom.” In the background of the video, people in bulletproof vests moved around, holding submachine guns.

In 2016, while hiding in the mountains, the Dwarf was interviewed by Rolling Stone. At that time, the pressure was mounting, and he could not easily return to his village to see his 88-year-old mother, Consuelo. The name Consuelo means comfort and solace in Spanish. The Dwarf often spoke about his perfect relationship with his mother, who was his emotional support, and he expressed great respect, love, and affection for her.

The Dwarf’s village was poor, with no job opportunities, but he still remembered how his mother made bread to support the family. “We sold the bread my mother made, and I also sold oranges, soft drinks, and candy. My mother was especially hardworking. We grew corn and beans, and I helped my grandfather with the cattle and firewood.”

“To afford food and survive, the only way was to grow marijuana and poppies. So, after I turned 15, I started growing these things and then selling them.”

In a 2018 interview with Time magazine, the Dwarf’s mother said, “Since he was a child, he has always fought for a better life. He always acted strong, as if everything would be fine.” The Dwarf remarked, “My mother knows me better than I know myself.”

The Dwarf inherited his mother’s work ethic and took the drug business seriously. According to witnesses, if an underling was late with a delivery, the Dwarf would order them to be shot. Being disloyal to the Dwarf was considered an unwise choice. His previously impoverished life, which required constant searching for a way out, perhaps honed his keen business instincts.

In the early 21st century, while the U.S. intensified its crackdown on Colombian drug trafficking, the Dwarf saw a market opportunity and began leading the transport of Latin American drugs into North America, resulting in exponential profit growth.

At the same time, the ambitious Dwarf continuously cultivated a global drug production network. For instance, a Mexican citizen named Ye Zhenli, who graduated from East China University of Political Science and Law, was accused of collaborating with him to purchase thousands of tons of cold medicine from China to refine methamphetamine. According to reports from The Washington Post and The New York Times, by the time of his arrest in 2014, the Dwarf had become the person who transported the most drugs to the U.S. in history, including 500 tons of cocaine. Over the past 20 years, the number of Americans dying from drug overdoses increased from 50 per day to 200 per day. On every continent, there were traces of the Dwarf’s drugs. He once said, “There is no place in the world where business is difficult for me.” Perhaps no one else would dare to say that, except for the Dwarf.

The prosecution lacked evidence of the criminal organization’s presence.

Frequent international business trips made the Dwarf and his underlings’ entry and exit data crucial evidence for the prosecution.

The prosecution brought in Colombian immigration officials to explain the Spanish entry and exit records to the jury, hoping to convince them of the validity of this evidence chain. However, the entry and exit records projected were small and dense, and the witness’s words needed to be translated from Spanish to English on-site, while the prosecution’s English was translated back into Spanish. This back-and-forth made it difficult for the twelve jurors, who had no legal training, to focus for four months.

At this point, 53-year-old defense attorney Jeffrey took the stage. He became famous for defending John A. “Junior” Gotti, the head of the Italian Mafia, ten years ago. At that time, Gotti faced 11 felony charges, including extortion and money laundering, and Richman crafted a narrative that after Gotti’s father was imprisoned, Junior took on significant responsibilities and inherited the Gambino crime family’s leadership, but he had not committed any crimes since his release in 1999.

Jeffrey’s defense of Junior Gotti led to a hung jury, resulting in a mistrial; the prosecution retried the case with a new jury, but they also could not reach a consensus. This back-and-forth continued for five years until the fourth trial, when the prosecution finally decided to drop the case, and Junior Gotti was acquitted. On the day of the court’s ruling, Junior Gotti’s mother cried, saying, “I want to get Junior Gotti out of this country; he will always be catnip for these people.”

Catnip is commonly known as a cat’s aphrodisiac.

At the Dwarf’s trial, Jeffrey took the stage to cross-examine the immigration officials brought in by the prosecution. This process is legally known as cross-examination. In 2016, he published an article titled “The Deadly Ace in the Hole—Cross-Examination, an Art That Seems to Have Been Lost.” In it, he claimed that cross-examination could not only destroy testimony but also undermine the government’s credibility and the evidence and opportunities that led to the suspect’s conviction. He wrote with exceptional confidence, as if he had reached a masterful level in this art. He stated that the first trick of the ace in the hole was to ask the witness a direct question that would make them nervous right after taking the stand.

Jeffrey: Is it possible for someone to enter Colombia with a fake passport?

Witness: We use various means to ensure that only genuine passports are used for entry.

Jeffrey: Can you guarantee that all entries are by the actual person?

Witness: For example, if identical twins enter with someone else’s passport, it can be a bit difficult, but we have a professional team to ensure that the entries are by the actual person.

Jeffrey, pressing further: Can you guarantee that there will be no mistakes?

Witness: … No, but we try our best.

Jeffrey: Is it possible for a genuine passport to be used for entry while the actual person does not enter?

The witness falls silent.

The jury remains silent.

The entire courtroom suddenly falls silent: even if the dwarf and his team enter with passports, it does not mean they are physically present—there is no evidence from the prosecution that the criminal gang was present.

Jeffrey certainly knows the effect his performance has created. He confidently steps down from the stand, smiles at the front row of the audience, and gestures with his hands as if to say, “How’s that? Is it good enough?”

At that moment, the courtroom doors suddenly open, and two little girls enter. They are dressed in all-white coats, with innocent and cheerful smiles. Their mother, with her hair cascading down, light lipstick, fresh and graceful, possesses the unique beauty of a Latin American woman. Under her guidance, the two little girls joyfully enter the audience area, taking their seats in the defendant’s family section. These are the legendary dwarf’s 7-year-old twin daughters and his fourth wife, Emma, who is 28 years old.

The beauty queen and the drug lord’s love story.

The 3-meter-long defendant’s family section is empty except for them. The little girls sit on the benches, leaning against the seats, swinging their legs.

This is the first time the little girls have appeared before the jury. This day marks the last court session before the Christmas holiday. An elderly woman in the audience, holding a stack of greeting cards, cheerfully writes Christmas wishes for her friends and family. All of North America is entering a lazy yet excited state. The scent of Christmas trees, the jingling of bells, crowded stores filled with shoppers buying gifts for loved ones, along with reunions, kisses, and hugs, create the perfect atmosphere for the end of a busy year.

Meanwhile, the little daughters and their mother are 10 meters away from their father and husband, reuniting. Their father watches them intently. The defense attorney had previously requested the judge to allow Emma and her husband to embrace for humanitarian reasons, but it was denied. The reason given was that the dwarf, who had successfully escaped from prison twice, might send coded messages to his wife. Emma became a beauty queen in a small town in Durango, Mexico, at the age of 18, and married the dwarf the same year.

There are romantic narratives about their union online, as well as criticisms that there is nothing romantic about a drug lord and a woman; the dwarf is merely using his wife to clean up his image. Nevertheless, when Emma was interviewed by the Spanish-language television channel Telemundo in early December and asked, “Every day when you walk into the courtroom, the dwarf’s eyes light up. How does that make you feel? As reporters who are there every day, we have never seen him like this,” she laughed heartily and replied, “I feel very happy. Seeing him smile makes me feel a bit more relaxed, thinking that things will get better. In the courtroom, I am obviously the only person he knows. So every time he appears in court, he looks for me, and that feeling of seeing someone you know among all the strangers is mutual.”

When Emma and the girls appeared, all attention in the courtroom shifted. Unbeknownst to them, they had become the center of attention, playing in the defendant’s area. I sat in the same row as them, and when our eyes met, the children seemed happy, shy, and puzzled—perhaps wondering, “Why are you looking at me?”

Telemundo’s interview once asked Emma what kind of life she wanted. She said, “I just want to live quietly and be treated like a normal person.” Just because they are related to the dwarf, people easily imagine how their lives differ from those of normal people, and under the spotlight, every move is magnified and interpreted.

The little girl sat on Emma’s lap and waved to her father, who waved back. Reports say that the father shed tears, but I was seated too far from the dwarf to see such details; I could only see him continuously looking in the direction of his wife and daughters.

Regarding whether this simple wave of interaction between father and daughter would affect the jury, the defense attorney stated in a CBS television interview, “As defense attorneys, one thing we always like to do is make our clients appear more human. Because in the government’s description, they are always the worst people in the world.”

People are easily moved by familial love and warmth, and so are jurors. If two people from different worlds are like isolated islands, then emotions are the carrier pigeons that connect these two islands. But aside from playing the family card, lawyers may resort to unconventional tactics to win the trial.

The music before the murder.

Defense attorney Edward Balarezo once tweeted a very cheerful Spanish country song titled “A Handful of Dirt,” which, according to witnesses, is the dwarf’s favorite music. The lyrics are simple, poetic, and carefree: “Life is like a dream for me. Life is short, do what you love. The world is unpredictable; only memories can remain. When I die, I will only take a handful of dirt with me.”

The prosecution immediately wrote to the court the next day, requesting the court to admonish Edward, stating in the letter, “Edward’s tweet is intended to intimidate the jury and witnesses.” The prosecution referred to the previous day’s court session, where a witness testified that before the dwarf hired someone to kill him, he had hired a band to play this song 20 times outside his prison.

The prosecution firmly asserted that this bizarre tweet could lead to an unfair trial. Edward, however, dismissed this as nonsense, arguing that the jury is not allowed to go online for related information and that “the government has endless resources, which allows you to waste time on such trivial matters.”

Edward, who graduated from the prestigious Georgetown University with a degree in political science and government in 1988, scolded the prosecution in a letter to the judge 30 years later: “Perhaps the government should spend more time organizing its materials; otherwise, it will waste the judicial resources it enjoys over the next few months.”

At noon, the courtroom doors opened again, and the prosecution’s witness entered, taking an oath.

“Your Honor… I… I’m sorry… I… I called the wrong witness…” the prosecution attorney suddenly said at the inquiry stand.

The courtroom fell silent for a second, then erupted in laughter.

The laughter of “Voldemort” was the most piercing, not a kind-hearted humor, but a stinging mockery and exaggerated performance. His team was already laughing uncontrollably. The prosecution team was momentarily thrown into disarray. The attorney who made the mistake was nervous, but caught up in the laughter of the audience, he pressed his lips tightly together, holding in a mouthful of air to avoid laughing himself, looking comically awkward like the British comedian Mr. Bean.

“Your Honor, please… allow me to correct my mistake,” he said, amidst the laughter.

After being permitted, he called the next witness, but the witness did not appear.

After a long two minutes, the door still did not open. “Hey, I’ll give you 60 more seconds,” the judge said.

Mr. Bean, anxious, stepped down from the stand, intending to go find the witness himself. His companion quickly stopped his madness. One minute passed. Another 30 seconds went by. Mr. Bean looked at the door, then at the judge, then back at the door.

Finally, the door opened, and a uniformed witness appeared.

This laughter continued into the elevator during lunchtime, extending to the cafeteria, adding a splash of color to the morning trial. The prosecution lawyers appeared deflated, like punctured balloons, making them seem even more unprofessional and untrustworthy. In contrast, the defense lawyers were humorous, skilled performers, cutting through the prosecution’s evidence chain, which resembled an old woman’s smelly rag.

During lunch, I stood in the long line at the cafeteria and finally sat down to eat. Emma and her two daughters sat about a meter away from me. Emma was eating a box of vibrant green vegetable salad, occasionally snacking on some chips. Her two daughters, joyful by nature, were running and playing in the spacious cafeteria. The three defense lawyers soon joined them, chatting and laughing together, creating a relaxed atmosphere reminiscent of a mother taking her daughters on a spring picnic with their father’s friends. The morning trial seemed to have placed little pressure on them.

After an hour’s break, the post-lunch trial felt increasingly tedious. The food in everyone’s stomachs was digesting, creating a warm, hypnotic atmosphere, and the wooden decor seemed to dissolve the authority of the eagle emblem of justice displayed in the center of the courtroom.

However, the prosecution, having been laughed at by the entire court, needed to regain their composure. The trial began, and everyone stood up.

“Ah-choo!” A thunderous sneeze echoed throughout the courtroom. Everyone turned to Mr. Bean, and the crowd collectively exclaimed, “God bless you,” accompanied by chuckles.

After the awkwardness of the morning, the prosecution sent a sweet-voiced, professional young female lawyer to present some photos of seized firearms, showcasing a floor littered with AK-47s. The dwarf’s daughters were playing, occasionally making noises. They had been in the courtroom for over two hours and were starting to fidget, prompting their mother to try to quiet them down.

Suddenly, the door swung open, and two large carts rolled in, filled with evidence. One cart was packed with AK-47 assault rifles, while the other was loaded with bulletproof vests and rocket launchers, causing the crowd to stir.

“Voldemort” was no longer at ease. He was trying to control himself, shifting from genuine laughter to forced smiles, striving to maintain an air of confidence. However, the young female assistant beside him instantly transformed her expression from relaxed to tense.

In the center of the courtroom, a witness picked up a firearm and began explaining how it operated, detailing how to load the bullets and the firing mechanism. I was fixated on where the gun’s muzzle was pointing. The prosecution suddenly asked, “You ensured these handguns won’t accidentally discharge in the courtroom, right?” The employee replied, “Uh, yes, I… I checked them all this morning.” With two televisions and a large projector in the courtroom displaying photos of the seized AK-47s, the reality of violence began to feel tangible.

Despite the defense’s various tactics to manipulate the jury, facing such a display of violence brought in on those carts, or dealing with such a complex case, likely made everyone feel the need for some external assistance or luck.

Sean Penn, the “Best Actor,” sought out the “Drug Lord.”

Whether motivated by prayer or not, according to the New York Post, a 15-centimeter tall statue of a Mexican folk hero, Jesus Malverde, was present in the defense lawyers’ meeting room next to the courtroom. According to folklore, this man was a drug trafficker but was celebrated in Mexico as the “Drug Saint” for robbing the rich to help the poor.

In the dwarf’s village, people also recounted how he suddenly appeared during religious festivals, distributing bundles of cash to villagers. “The dwarf is a leader and a hero to the locals. He is a farmer who started from the bottom but helps others,” said Baldomaro, a teacher near the dwarf’s village, to Time magazine. “He paves the way for the sick and pays for their medical expenses.” In contrast, the Mexican government has failed to provide even the most basic infrastructure in these remote, impoverished rural areas.

Regarding the dwarf’s drug empire and the killings he orchestrated, Rolling Stone once asked him:

“Drugs cause harm and destroy humanity. Do you think that’s true?”

“Yes. But unfortunately, in the place where I grew up, there was no other way for us to survive.”

“Do you think you should be responsible for so many drug users in the world?”

“No, that’s a wrong way of thinking. Drug trafficking is also a misnomer. Without consumption, there is no sale. Even if I were gone, drugs wouldn’t disappear. People always want to know what it’s like to use drugs.”

In the courtroom, the dwarf’s young daughters were becoming restless, chirping as if they were singing.

Just a few minutes after the firearms were presented, their mother took them away, and they did not return.

“What dreams do you have for your life?”

“I want to live with my family for as long as God grants me time,” the dwarf said in a video interview with Rolling Stone.

“He hopes everyone can see him from another perspective. He is a person, a friend, a father—essentially a normal person,” Emma emphasized during an interview with Telemundo. She explained that this was why the dwarf took the risk of being interviewed by Rolling Stone, as American actor Sean Penn wanted to plan a movie about him. The dwarf desperately wanted to portray himself as a “normal person.”

After the interview concluded, the dwarf was arrested.

After the day’s trial, the judge, like a homeroom teacher, addressed everyone before they left for the holidays.

“I want to remind the jurors to please adhere to the rules. Do not contact the media, do not search for information related to this case online, and do not discuss the details of the case with friends, family, or anyone else. Your only sources of information regarding this case should come from what the prosecution and defense present in this courtroom, and you should base your judgments solely on that.”

“Finally, I wish you all a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.”

The crowd dispersed. The defense lawyers walked into the press area, chatting and laughing with reporters. In the elevator, a reporter from a Mexican television station remarked, “This is quite a show. But these defense lawyers are really funny.”

As of the time of this report, the entire United States was slowly wrapping up the New Year holiday, but the dwarf and his dream defense team were facing another wave of intense scrutiny: the dwarf’s IT engineer had been turned by the FBI—prosecution obtained recordings of the dwarf’s phone communications dating back to 2011. In one call with the Mexican national police, the dwarf asked, “Did you receive the allowances we send every month?”

In another call with one of his subordinates, the dwarf said, “Don’t be too harsh on the police; they are helping us.” The subordinate replied, “Really? But you taught us to act like wolves.”