This is an AI translation from the original Chinese version.

If most bookstores in the world are refined and elegant, Strand is a testament to the creator’s favoritism—it is wild and vast. The four-story building is filled with books, housing limited editions of “Ulysses” signed by James Joyce and painter Henri Matisse, treasure-laden dollar book shelves, and banned books collected by the old owner during his service in West Germany. Visitors are drawn here, from Michael Jackson taking moonwalks to a swaying drifter, an untamed Bob Dylan, and a Japanese tourist who bought 300 tote bags in one go.

For nearly a century, nothing has truly constrained it, whether it was the high rents in downtown New York, the Great Depression of the early 20th century, World War II, 9/11, or the rise of e-books. It has become the largest used bookstore in the world, a birthplace for artists and a sanctuary for the soul, standing tall at the center of New York’s publishing, writing, and art scene.

However, time is ultimately the greatest adversary. After 93 years of operation, the COVID-19 pandemic swept through New York. Now, the bookstore, barely surviving after the fierce battle, is wedged between rows of shuttered shops, fighting against death with the stubbornness that runs in the Bass family blood.

The Fall

The pandemic in New York has lasted for ten months. Now, the shelves that were once overflowing with books at Strand have become sparse, with some half-empty; the iconic selection of writing and script shelves have disappeared; the few remaining employees hurry about; and the sparse customers wear expressions of isolation from their own worlds.

Sitting across from me is Nancy Bass, the third-generation owner of the bookstore, who appears very fatigued, often drifting off mid-sentence, her breath weak. Clad in a red sweater, she tries to appear upbeat, but she is too exhausted. She has been shouldering the weight of the bookstore, filled with hopes and legends, navigating through storm after storm to reach this point. At 59, she tells me she will do anything necessary for the survival of Strand.

Everything came too suddenly. After the first COVID-19 case was confirmed in New York in March 2020, Nancy urgently closed the store and laid off 188 employees. Soon after, the number of cases in New York skyrocketed to ten thousand. Just as the cacophony of sirens began to ease, people poured out, vandalizing the bookstore’s entrance and burning police cars in protest of the police killing of George Floyd, while officers aimed their guns at the crowd. Amid the tumult of riots and looting, her mother’s frail breath faded. On June 1, her mother passed away alone, fearing infection, without even a farewell gathering.

Sometimes, Nancy wanders the empty store alone during the day. The once vibrant bookstore, filled with the scents of humanity, old books, and excitement, has been replaced by disinfectants and the smell of cleaning agents, killing every possible COVID-19 virus and everything else. Reflecting on those days, Nancy falls into a long silence: “The bookstore was empty, so sad, like a haunted house.” At night, she often tosses and turns, and when she finally falls asleep, she dreams of the elevator she is in suddenly beginning to fall.

At times, she calls fellow bookstore owners for support. No one can explain what this all means, not even the largest independent bookstore in the world, Powell’s City of Books, the super-chain Barnes & Noble, or smaller stores like Three Lives. No one wants to say it means death. According to the American Booksellers Association, since the pandemic began, about one independent bookstore has closed each week in the U.S., many crushed by rent. Although Strand purchased the entire building 19 years ago and does not pay rent, the pandemic can still drain all resources.

Sometimes, she just wants to escape. She rereads Jane Austen, follows Nancy Drew in solving several cases, and reads anything that can uplift her spirits. She also reads celebrity autobiographies, including that of British rock star Elton John. She enjoys stories with elements of personal heroism, seeing how ordinary people become great through adversity, just like her father, Fred Bass.

Wild as a Mustang

Strand has faced closure more than once. In 1956, rising rents made it difficult for the small store to survive. While over forty other booksellers on the same street lamented their fate, 28-year-old Fred moved the bookstore to its current location at the corner of Broadway and 12th Street, renting a larger space and paying four times the rent. Other booksellers thought he was crazy, but playing by the rules was not Fred’s style: he decided to use an increasingly larger store and more revenue to pay the higher rent.

The era of Strand’s wild expansion began with Fred’s old book acquisition table.

Every day at that table, Fred, always in a shirt and tie, welcomed unexpected guests from all directions, a diverse mix like New York itself: students, writers, other bookstore owners, drifters, and more. Sometimes these visitors didn’t even know they were bringing valuable items, like a book with a love letter tucked inside or a 1632 edition of Shakespeare worth $100,000. The treasures often made Fred’s heart race with excitement, and treasure hunting became his greatest passion.

In the early days of scarcity, Fred collected every book he could find. When he couldn’t gather enough, he would go to private homes, libraries, or even the discarded unsold book bins of other bookstores; he collaborated with media and critics to acquire free book samples at low prices; and when one New York wasn’t enough, he would fly abroad. As his choices expanded, he said, “You have to be willing to take risks and experiment, to see the world beyond the books in front of you and what you know.”

He became addicted to collecting books, desperately needing to see them fly onto the shelves until they were nearly overflowing. When they could no longer fit, he expanded. In ten years, Strand’s collection grew from 70,000 to 500,000, and by the 1990s, it reached 2.5 million, stretching 37 kilometers, with updates every 1-2 years, making Strand the largest art bookstore in New York, often with excess inventory.

Fred’s greatest ambition in life was not to create a bookstore that could convey a certain ideology, but to have a very large and magnificent bookstore that would attract people like a magnet. And he succeeded: the vast, high-quality, and affordable used books made the store wild as a mustang, as expansive as the ocean, influencing a diverse array of people in New York.

Author Paul Krugman, a regular at the store, once said, “In this digital age, you can always find what you’re looking for. But in a good bookstore, you can encounter books you didn’t know you needed, which can change your life. A truly great bookstore is filled with such books everywhere. Strand is the greatest bookstore in the world; no other bookstore is like it. It has never degraded into something lesser; it is an invaluable resource for New York and the world.”

In Strand’s immortality, there is not only Fred’s madness but also Nancy’s innovations for the bookstore, as she, a graduate with an MBA, firmly believes that Strand needs to be guided forward by modern means.

Starting at the age of 25, Nancy has worked at Strand for over 30 years, managing websites, opening pop-up shops, creating merchandise, developing public spaces, and hosting events, weddings, parties, and cocktail receptions. She even established a custom book department, selling entire bookshelves or walls of books. This department was so successful that it helped the film “A Beautiful Mind” find 1950s math books, designed a prison library for the TV series “Oz,” and created 35 libraries for a Manhattan resident with 35 rooms.

The side businesses Nancy developed contributed up to 30% of the bookstore’s revenue at their peak. While Fred lamented that Amazon was taking over the world, Nancy always believed in the future of independent bookstores. She led Strand against the odds, achieving a steady annual profit growth of 7-10%. However, Fred always disliked installing air conditioning in the bookstore. The Wall Street Journal joked that perhaps Fred preferred the suffocating heat among the towering bookshelves.

The father-daughter management dynamic ended two years ago with Fred’s passing. Now, Nancy is left alone.

After finally reopening on June 22, 2020, the real nightmare began.

Nancy thought New York was returning to normal and quickly rehired about 55 employees. However, two weeks later, the store had almost no customers, and even the New York subway faced bankruptcy due to a drastic drop in ridership. Nancy had to urgently lay off 12 union employees, explaining that each of them cost her $5,200 a month. The government’s one or two million dollars in payroll assistance would only help the bookstore survive for another 2-4 months.

But the employees did not see it that way. They had also endured three months of isolation, riots, and life pressures, and the layoffs quickly turned their negative emotions into anger towards Nancy. Will Bobrowski, a union representative who had worked at Strand for 18 years, described Nancy as foolish, cruel, and fickle, extinguishing the enthusiasm for returning to work. Some accused Nancy of using the relief funds not to rehire employees but to buy stocks in her independent bookstore’s rival, Amazon.

Between April 6 and September 1, 2020, Nancy, like her father, made 167 stock purchases, including $220,000 to $600,000 worth of Amazon shares. Employees launched an online campaign against Nancy, even protesting outside the bookstore, forcing her to welcome customers inside.

As for whether Nancy used relief funds to buy stocks, Will stated, “As a union representative, I have never made such an accusation against her. Honestly, I don’t think she would do that.”

While the lower-level employees were in turmoil, Nancy also fired several middle managers, including Randy Sterling, the distribution manager. Randy, who had worked at the bookstore for 14 years, speculated that he was let go because he initially refused to come to work out of fear of infection, giving Nancy the opportunity to dismiss managers she disliked. Eddie Sutton, the general manager, also left. After 30 years, Eddie had risen from janitor to general manager, assisting both Fred and Nancy, treating the bookstore like home. No one knows what exactly transpired between him and Nancy.

In the eyes of union employee Uzodinma Okehi, the protests reflected another possibility: “In America, there are many class issues. Sometimes employees are just jealous that she is a millionaire, envious that she inherited this store, and feel she doesn’t deserve it. Both sides have exaggerated their claims, and there are too many absurdities; they should make a reality show about it.”

Fred used to joke about the wild employees at Strand when he was alive. Sometimes, new hires would transform from a suited gentleman into a tie-dye shirt-wearing buddy as soon as they passed their probation. Fred would say, “Is that the person I just hired yesterday?”

Uzodinma, now 43, graduated with a master’s in creative writing from New York University and has worked at Strand for 13 years, primarily in the shipping department. He said Strand provided him with stability, allowing him to write without financial worries. Unlike the Barnes & Noble bookstore where he previously worked, Strand not only provided excellent insurance but also showcased his book, “Over For Rockwell,” as soon as it was published in 2015.

Uzodinma is not the first author to move books at Strand. The bookstore’s most famous former employee is Patti Smith, who became the godmother of American punk. In 1974, at the age of 28, she worked at Strand but hated the job—perhaps because her basement workspace was infested with cockroaches and mice. Now, her new book is prominently displayed at the entrance of Strand.

Strand also employs individuals from diverse backgrounds. For instance, Randy, the distribution manager, originally studied culinary arts. He admitted to only getting three answers right on the quiz, as he wasn’t particularly fond of reading, but he enjoyed fantasy and children’s books, so recommending Dr. Seuss’s charming picture books was no problem. During his interview, he said, “I’m a big guy, willing to do heavy work. Can you put me in the warehouse to move books?” He felt he was hired because of his good nature.

Will, the outspoken union representative, shared that when he first arrived in New York, he was a clueless 22-year-old with a physics degree that seemed useless in the job market. Surprisingly, he excelled in the bookstore, where liberal arts employees were abundant, thanks to his strong science background. He found the quiz easy and spent years exploring topics like neuroscience, computer science, music, and history in the basement, often encountering forgotten 19th and 20th-century books, pricing them based on taste, and enjoying himself immensely.

Survivor

Fred always managed to connect with the wild employees, perhaps because he was a wild one himself. His favorite artist was the Fauvist painter Henri Matisse, and he had a childhood penchant for vandalizing fire hydrants and setting fires, watching firefighters rush in, helplessly trying to disperse the mischievous children.

As an adult, he would sit at the used book acquisition desk, lending money to employees when they needed it, ranging from a few dollars to tens of thousands, without requiring signatures or charging interest. Will remarked, “What boss can do that?”

I asked Will how much he had borrowed from Fred and what he had used it for.

He suddenly transformed from a combative union negotiator into a boy caught in a web of small schemes. He said, “Oh, I once borrowed a thousand. My computer broke, and I needed 800 dollars for a new one, plus another 200 dollars for utilities and internet fees. But some people have borrowed ten thousand; it’s crazy.”

When we video chatted, Will had a photo of Lenin hanging behind him. He said his favorite writer was Marx and that he was a passionate Marxist, naturally opposing class differences. However, he greatly admired Fred. Lending money to employees was just one aspect; Fred also helped those with drug problems find appropriate support centers, funded charity projects for the elderly, and enjoyed donating money. In his unique way, Fred dissolved the class struggle defined by Marx and, to some extent, realized the ideal society described in the “Communist Manifesto”: everyone should contribute according to their ability, and everyone should receive according to their needs.

However, the more one experienced Fred’s old-fashioned, personal management style, the less adaptable they became to Nancy’s management. In 2011, as Nancy gradually took power, she attempted to significantly cut employee benefits. Will described Nancy as being consumed by her MBA mindset, always thinking about cutting costs and increasing revenue, completely lacking respect for people. After Nancy took control, lending money became impossible. In a 2017 interview with NPR, Fred stated that Nancy’s management was intolerant of any mediocrity, deception, or lies.

Regardless, the outcome was that Will said, “I’m willing to work hard to help Fred make money, but I don’t want to help Nancy make money.” For a long time, many long-time employees like Will, who had worked at Strand for twenty or even forty years, helped stabilize the bookstore’s operations and atmosphere. But now, the backroom was turbulent, and sales in the front were dismal; even the September back-to-school season did not improve the situation. Nancy’s nightmare finally became a reality—the bookstore could not hold on any longer.

She often told people that Strand was the last survivor of the once-thriving book street. Between 1890 and 1960, the bustling Fourth Avenue had 48 bookstores, most of which were second-hand shops, many opened by Jewish immigrants. Together with the surrounding galleries, theaters, music clubs, and the vibrant ideas and free-spirited artists, they nurtured Greenwich Village. The glorious history left behind names that are easily recognizable: William Faulkner—who once moved books on the street and later won the Nobel Prize in Literature, and Allen Ginsberg—the spiritual leader and poet of the “Beat Generation,” who often wandered around Strand, among others.

Carrying the glory and ambition of the lost book street, along with the love passed down from her grandfather and father, she felt panic, fear, and loneliness as she held the reins of time.

She recalled her childhood growing up in Strand. At five, she could help staff sharpen pencils or patter around on the old wooden floor in her little shoes, looking at various candy-colored children’s books, astonished to learn that she could take any book home as long as she liked it. When she was engrossed in reading, someone would come to call her, “Nancy, it’s time for dinner.” After starting school, when a teacher asked Nancy to buy books, Fred would gather them for her, allowing her to take them to school for free. At sixteen, she began working part-time in the store, answering phones and handling cash. As she grew up, she sometimes foolishly wondered, “What if I were a doctor?” But no, she only wanted to work at Strand; there was no better place than a bookstore, just as her father often said, working in a bookstore was the best job in the world.

“If tomorrow were the end of the world, and there were only 24 hours left, what would you do?” a reporter once asked Nancy.

“I would stay in the bookstore. I love it here; I really do.”

This sentiment was much like her grandfather’s. In 1927, Benjamin, a poor Lithuanian immigrant, founded Strand at the age of 26. Two years after opening, the bookstore faced a decade-long Great Depression. According to the New York Times, he had to live in the store, sleeping on a small bed behind the shop to keep it afloat, while sending his young children to foster care. But his wife soon passed away due to illness, and Benjamin fell behind on rent for two to three years. He held on until a kind landlord granted him a rent extension, allowing Strand to survive the despair.

For 59 years, Strand has grown into a soft and passionate presence in Nancy’s heart. To maintain the bookstore, she was willing to become the person in the eyes of employees who could be almost ruthlessly cold to achieve her goals. Compared to Fred, who could always tell stories succinctly and humorously and was loved by many, Nancy was not smooth or adaptable—she always fought alone.

But the pandemic and crises do not believe in individualism.

In late October 2020, Nancy called everyone together for the first time, took the microphone, and stood on a platform: Strand was in a critical situation, and she pleaded for everyone to temporarily set aside their differences and work together to help save Strand.

“Nancy seemed like she was about to cry as she spoke,” said You. Regardless of whether these long-time employees, who had been left by their fathers, had been hurt by her or understood her, her sincerity once again brought everyone’s hearts back to Strand, the bookstore that three generations had built together and that everyone loved. You said, “After hearing her, we thought, let’s put everything aside and save the bookstore together!”

A few days later, on October 23, she posted a plea for help on social media:

“Due to the pandemic, the bookstore’s sales have dropped by 70% compared to last year. Our survival depends on the next few months… I once watched my grandfather and father side by side appraising used books at the store, and I never imagined that one day the bookstore’s financial situation would be so dire that I would have to write to friends and loyal customers for help. Writing this letter breaks my heart, but this is our current predicament. My grandfather and father worked in this bookstore six days a week their entire lives; I don’t believe they would want me to do nothing and give up. For the printed world we all love, I will do my utmost.”

At the end of the letter, Nancy left her office phone number and personal email.

The Roller Coaster

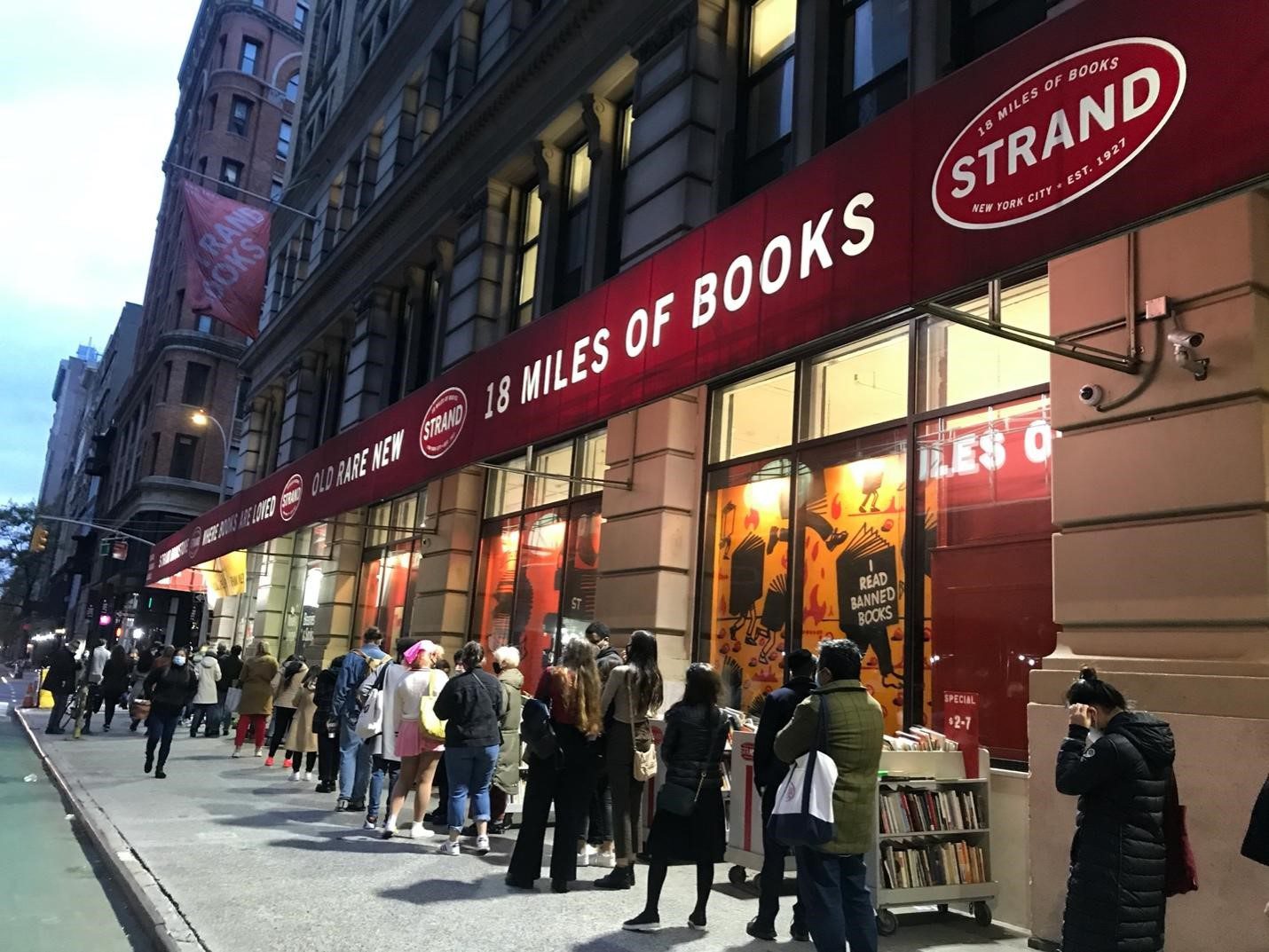

Nancy expected some help, but she never anticipated that within just half an hour, the bookstore’s website would crash due to overwhelming traffic. Within 48 hours, there were 50,000 orders, 80 times the usual amount; shipping addresses included not only New York but also Singapore, Milan, and other places around the world. Some people bought 197 books in one go; others sent her checks; some delivered free pizza and coffee to the bookstore; readers lined up outside the store despite the pandemic; not only the mayor of New York showed up, but also the person who had stolen a William Blake book from the store eight years ago—this time, he not only brought a small note of apology but also included 20 dollars. Nancy said, “Oh my God, it felt like a roller coaster; the outpouring of love completely overwhelmed me.”

The line of people outside the bookstore

The apology from the book thief

This love has always been mutual. Inside the bookstore, there were large red and white signs saying “Can we help you?” or friendly little signs saying “Welcome, book lovers.” Together with the knowledgeable and friendly staff, the bookstore created an atmosphere that made people feel that even if they didn’t buy anything, it was good to come in and read; Strand welcomed everyone.

In early November 2020, I visited Strand and saw John browsing discounted books at the entrance. He carefully examined each row of small carts, completely absorbed among the shelves. John wore a mask that revealed his large nose, and he spoke sometimes with a stutter. His dirty coat was not only full of holes that let in the cold wind but also contained a copy of “The Iron Cross”—a biography written by German Air Force General Adolf Galland during World War II. He said he had loved reading his entire life, enjoyed literature, history, and philosophy, and admired Shakespeare, Edward Gibbon, and Aristotle.

In the midst of his daily struggles with homelessness, finding shelter, and paying various bills, reading these books has been very important to him.

On the left is John, photo by Chen Teng.

I asked him what his last name was. He replied, “I’d rather not tell you, as I was the main witness in a murder case in Queens several years ago.” However, he did share that he believes Strand is the best bookstore, one that cannot be found anywhere else in the world.

It’s not just John who appears impoverished in the bookstore. On the first floor, a woman leans against a bookshelf, lazily immersed in the last few pages of a hefty book, with three recycling bags beside her and wearing tattered shoes. I then went to the second floor, where I saw a short Hispanic man, dressed like a construction worker, engrossed in flipping through books about jewelry.

This sense of equality and inclusivity may also be related to Grandpa Nancy’s humble beginnings. Benjamin, who came to New York at 17, started as a low-level worker, having worked as a carpenter, subway worker, mailman, and fabric salesman. It was his passionate love for reading at lunchtime that led to the creation of Strand.

Fred, who grew up during the Great Depression, spent his childhood in foster care. In 2017, he and his daughter participated in an oral history project in Greenwich Village. His daughter recounted that during his time in foster care, Fred often had to eat leftover food from others. Every weekend, the children would receive small rewards, and Fred could choose between buttered toast and crumb cake, but he could only pick one. When Nancy asked him which he preferred, he said he liked both. Perhaps due to these childhood memories, Fred dedicated his life to “taking good care of customers,” insisting that the store maintain a rough charm to avoid scaring away patrons. As a result, those drawn to Strand included not only writers and artists but also homeless individuals and various eccentric characters, as long as they wanted to read.

After coming down from the second floor, I noticed a young woman seemingly negotiating prices with the staff at the front desk. This 29-year-old philosophy PhD, Katherine Belle Merr, visits Strand four times a week and often browses the discounted old books at the entrance. She said, “Originally, these books started at $1, and you could find great treasures, but now they range from $2 to $7, which isn’t as good.”

However, Nancy did not hear Katherine’s complaints, nor did she hear the staff’s grievances.

With a sudden influx of orders, the bookstore’s normal capacity would require 160 days to fulfill. Nancy hired more staff and worked alongside them six days a week, putting in 9 to 12 hours each day to find, pack, and ship books. She said that the love from everyone made her want to fight harder. With Thanksgiving just a month away, she spent every day in the shipping department, striving to improve efficiency so that everyone could receive their orders in time. Before this, she had rarely been in the shipping department, and the staff had already developed their own way of working. Sometimes, she would tell them where to place chairs, which tables to switch, or that there were too many pens on the table, or that they needed to learn Amazon’s order processing—attending to every detail like a mother caring for a baby.

Fred expressed his respect for Nancy’s willingness to get involved, but he felt she was often counterproductive. One day, Nancy said she would help with packing. She took a basket of books to her office, and after a while, she emerged. The staff exchanged glances and fell silent as they looked at her packing. After Nancy left, they unpacked everything she had done and repacked it because she hadn’t included cardboard in the packaging, making the books prone to damage during transport, but no one dared to mention it in front of her.

Will, on the other hand, received daily complaints from the staff, saying that Nancy would sometimes appear out of nowhere and start giving various orders. “She doesn’t understand how we do things; she’s simply crazy. We have important tasks to keep the bookstore running, and we don’t need her interference.”

Perhaps the most significant change among all the shifts was the suspension of used book acquisitions, although recently released bestsellers were still selling well.

Fred had once insisted on placing the acquisition table, which bore the soul of the bookstore, at the entrance. He wanted customers to see that Strand was always acquiring books and to see every customer who entered the store. However, Nancy felt that the space taken up by the table could accommodate 1,000 more books. When the father and daughter were at an impasse, Fred stubbornly held his ground. One day, when Fred was on vacation, Nancy moved the table to the back of the hall, marking the end of Fred’s era. Now, the acquisition of used books has been suspended for nearly ten months.

After the call for help was sent out, two months passed. Stumbling through, Nancy led the bookstore through the Christmas shopping season and into the slow sales period when the virus surged again. New York State saw a resurgence of cases, with daily new infections exceeding 10,000, and on January 4, the first case of a variant virus was confirmed in the state.

On December 25, 2020, Nancy sent a message to readers: “Sometimes, I forget how many hearts Strand has touched in our 93-year history. But the past few months have reminded me that this legacy, started by my grandfather, holds personal significance for New Yorkers and book lovers around the world. As another lockdown approaches, we, like every other small business, are preparing. I promise to do my utmost to keep Strand alive.”